Bodaimoto

Bodaimoto 菩提酛 is a yeast starter method for sake making that came into prominent use in medieval Japan. Bodaimoto remained popular through the Edo period and into modern times, until around a century ago when kimoto and sokujo methods quickly gained favor among brewers. In recent decades bodaimoto has seen renewed interest by a number of sake breweries dedicated to its revival.

Bodaimoto has direct roots in a recipe for ‘Bodaisen’ sake found in the earliest guide to sake brewing, ‘Sake Journal’. Bodai 菩提 is the Japanese rendering of the Sanskrit term bodhi, meaning the awakened wisdom of a Buddha.[1] In turn this makes bodaimoto an “enlightened starter”. There is a similar linguistic connection to the Bodaisen Shoryaku-ji Temple 菩提山正暦寺 in Nara, the nearby mountain Bodaisan 菩提山 and the river Bodaisengawa 菩提仙川.

Shoryaku-ji Temple and Bodaisan mountain 菩提山 - Article, Source image

Contents

Process

The process of making bodaimoto can be considered a direct precursor to the modern sokujo ‘quick brewing’ method, as illuminated by Andrew Russell in “Bodaimoto - Brewing at the Buddha's Foot”. The comparison is based on the two-step method of first creating a lactic acid starter, followed by using the lactic water produced to build a yeast starter.

Microbially speaking though, bodaimoto shares much in common with kimoto and yamahai methods, making use of microbes present in the brewery environment. The main actors are an array of bacteria and wild yeasts that can transfer through the air, on tools, or simply reside in brewing vessels. In the bodaimoto process microbes also come from the water source and from the raw rice used in the process.[2] The complex microbial succession that’s required is not a sure thing, so the process is susceptible to spoilage by unwanted microbes. It follows that ‘seeding’ the soyashimizu with lactic cultures from a known source can provide insurance against spoilage.

The first step in making bodaimoto is to create the soyashimizu そやし水 (‘blessed water’) through lactic acid fermentation over several days.

The process currently used by the Bodai-ken group has been slightly revised from historical recipes, as paraphrased here.

Soyashimizu is made by soaking raw rice in a mesh bag in lactic cultured water at 25°C or above for 2 to 7 days until its pH falls below 4.0. The traditional approach included adding a small amount of boiled rice as an additional food source for the lactic bacteria, but the modern Bodai-ken version of bodaimoto omits this and still ferments thoroughly.

When CO2 starts to be released and the mixture is sufficiently acidified, the liquid portion is filtered out to become the soyashimizu. The soaked rice is then drained, steamed, cooled, and added back to the soyashimizu along with koji rice and yeast to build up the moto. The moto stage then takes several more days, allowing the yeast to replicate and develop.

Bodaimoto itself has many variations, and can be expertly manipulated by the brewer to produce virtually any style of sake. Much as kimoto can be used to create ultra-clean styles all the way through to rustic and strong tasting sake, so too can bodaimoto.

There is an interesting parallel between bodaimoto and a historical brewing practice in Okinawa. Chuko Awamori Distillery has revitalized a process called ‘shi-jiru’, in which raw rice is soaked in lactic water before being made into koji and then into awamori. Unlike bodaimoto however, only the rice goes on to be used in brewing while the lactic water is left behind to be re-used for soaking subsequent batches of raw rice.

History and seasonality

In the Muromachi period bodaimoto may have been used year round, reflecting that sake brewing took place in all seasons. Then from the 1670s onwards sake brewing shifted to becoming more of a seasonal affair from Fall through Spring. Early modern records (see Domou Shuzoki) show that bodaimoto was employed for brewing in late Summer when temperatures were starting to cool but were still too warm to carry out kimoto.

The high temperatures in late Summer sped up the initial fermentation process, and while that lead to quite a pungent smell, the resulting acidic water made a suitable environment for safely developing a yeast starter.

A recipe for making Dakusyu is given in a 2002 paper by Matsuzawa. Dakusyu (dakushu) was a lower grade style of ‘white’ temple sake in medieval Japan, what would now be considered a kind of doburoku. The process that follows is more modern than the one found in Goshu no nikki, being based on methods carried out at Okura Honke since the early Showa period.

For the soyashimizu: 60.5kg raw rice, 4.5kg boiled rice, 90L water. Soak for 6 days.

For the bodaimoto: Steam and add back the soaked raw rice, add 30kg koji (33% of total rice). This is a full sandan shikomi recipe.

Image reference: Matsuzawa, p2 [3].

Ikaki-moto 笊籬酛 is an alternate term for bodaimoto, named for the bamboo colander used to retain uncooked rice in the soyashi starter. The Matsuzawa paper gives other historical names for bodaimoto: 菩提泉 bodai-sen, 水酛 mizu (water) moto, 漬け酛 tsuke (pickle) moto, 旅籠酛(いかきもと) ikakimoto, 菊伍 kikugo, and 被酛 (かぶりもと) kaburimoto. The term mizu-moto is still in use today, often used to describe a process similar to bodaimoto. Mizu-moto is addressed by several sources linked in this article, but it is not given a full treatment here since its definition varies and has evolved over time (see Sake Deep Dive).

Timeline

1489 (or 1355) - Goshu no nikki written, see Recipes below.

1687 (approx.) - Domou Shuzoki written, see Recipes below.

1932 - In 2002 it is ‘discovered’ that Okura Honke 大倉本家, a brewery in Kashiba City, Nara, has been making doburoku shrine sake on behalf of the Nara Prefectural Shrine Office using a bodaimoto method since the early Showa period [3, Wikipedia]. Okura Honke’s website has a rich timeline of their history brewing shrine sake.

1986 - Tsuji Honten began experimenting with bodaimoto methods at their brewery.

1996 - The Bodai-ken group was formed at Shoryaku-ji Temple in Nara, a historically significant site for sake brewing. Once a year in January they prepare bodaimoto in a festival-like ceremony.

For a colorful view of the historical nuances and sequence of events, the Sake Deep Dive episode on bodaimoto is recommended listening.

Recipes

Goshu no nikki

Goshu no nikki, or ‘Sake Journal’ is the earliest guide to sake brewing. It contains the direct predecessor to bodaimoto as a recipe for Bodaisen 菩提泉, “Font of Enlightenment”, named after the Bodaisen River near Shoryaku-ji Temple.[1] The first English translation and analysis of all six recipes in Goshu no nikki was published by Eric C. Rath in 2021, shared here with permission.[4]

Font of Enlightenment (bodaisen)

Wash 18 liters of polished rice until the water is clear. Remove 1.8 liters of rice from that and cook it. In the summertime, be sure to allow the rice to cool thoroughly. Put that cooked rice in a bamboo basket and soak it in water, positioning it in the middle of the [remaining] uncooked rice. Seal the container for a day and let stand overnight. On the third day, place a bucket (oke) off to the side and remove any clear water at the top of the vessel. Then remove the cooked rice from the center and place it in the bucket off to the side. Next, remove the uncooked rice and thoroughly steam it. In the summer, be sure to allow that rice to cool completely. [From that rice prepare] 9 liters (5 sho) of koji and set aside 1.8 liters (1 sho) of it. Combine that 1.8 liters koji with the 1.8 liters of cooked rice [that had been soaking in the basket in the water] and place half of it flat on the bottom of a bucket. Combine the remaining [4 sho] koji with the rice, mixing these together and placing them in the fermentation (tsukuri). Measure off 1.8 liters of the [clear] water removed earlier and add that on top. Then spread the [other half of the] cooked rice [and koji] from earlier on top of that. Cover the opening with a straw mat; let it rest for seven days. The sake is usually done in seven days, but if you do not need it yet, wait up to ten days.

There are a couple interesting features to note in the recipe. One is that a ratio of 1:10 is given for the amount of steamed to raw rice to use in the initial soaking step, and another is that the soaked rice goes on to be used as the brewing rice in a single step moromi. A second recipe in Goshu no nikki is given for Nerinuki, ‘Glossy Silk’, using the same bodaimoto method with a longer soaking time. It produces a so-called white sake, which may have resembled a thick form of nigorizake.[4]

Domou Shuzoki

The Domou Shuzoki 童蒙酒造記 (author unknown) was written around 1687 in the Edo era, and it covers the ten or so regional brewing styles of the period, including ‘Bodai-sho’ 菩提性.[5]

Bodai-sho Brewing

Bodai-sho is brewed between July and September, when there is still lingering summer heat. The distinctive feature of this process is that a portion of the rice is soaked in water while it is still raw to induce lactic acid fermentation, thereby preventing the growth of bacteria. The brewing process is carried out in two batches: soe and tome. The pressing period is from 7 to 12/13 days after brewing in July and August, and from 14/15 to 20 days in September and October. Since it keeps well for a long time, it could be shipped to Edo (present-day Tokyo). [Translated by DeepL]

Bodai-ken

Bodai-ken 菩提研 is the shorthand name for the modern “Nara Sake Research Group for Producing Sake using Bodaimoto”. The group’s official website explains the history and motivation behind the bodaimoto revival that has taken place in Nara since 1996. Their main process takes place at the Bodaisen Shoryaku-ji Temple in Bodaiyama-cho, Nara City. Important to the choice of brewing location is the water source, which has been found to naturally contain the bacteria Lactococcus lactis subsp.lactis (L. l. lactis). A short video showing their equipment, ceremony, and process from 2017 can be viewed here, along with a clip showing the source of the water they use.

Rather than brewing bodaimoto in late Summer as was historically done, the Bodai-ken starter is made once a year in January. For the soyashimizu soaking phase they use only raw rice and local water. For the moto stage, about 480kg of Hinohikari (ヒノヒカリ) rice is steamed in preparation for addition to the moto. It takes about ten days to fully develop the yeast starter. It is unclear which strain of yeast they use; please contact the authors here if you have any details. The finished bodaimoto is divided up and distributed as an active yeast starter for use by eight participating breweries in the area.

Homebrew Recipe

This recipe produces a yeast starter and is not a finished sake recipe itself. It may be used as a moto to make 5L-12L of moromi or scaled up as needed. It requires no special equipment and is well suited to homebrewed sake.

Ingredients: 25g cooked rice (ferment and discard), 250g raw / uncooked rice for soaking, 450mL water or enough to cover, active lactic starter (optional, see note below), 100g koji, sake yeast (~20B cells, optional but recommended).

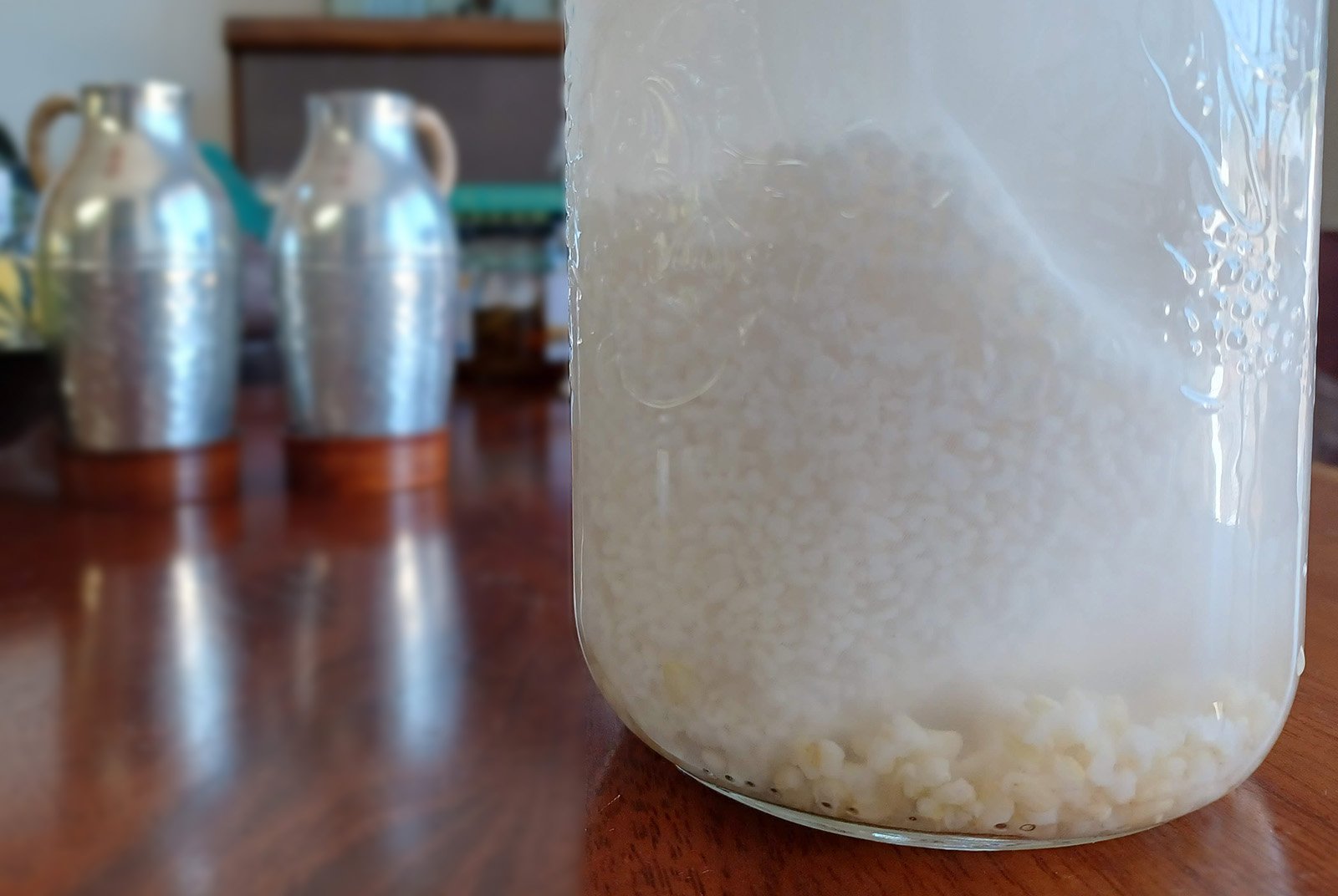

Process: Place the uncooked rice in a cloth or mesh strainer bag for later removal. Combine all ingredients except the koji and yeast in a jar, loosely covering it with a lid or cloth to allow gas to escape. Keep the jar at around 20-25°C. The exact temperature is not important but it will ferment faster the warmer it is. This first stage of fermentation may take 4-8 days depending on the temperature. CO2 bubbles may be seen during the most active period, with pungent acetic and lactic notes developing. These signs are useful to watch for, especially if you don’t have the means to test pH or total acidity.

Once a pH reading of 4.0 or less (3.6 ideal) or total acidity of >3.0 is reached, remove the soaking rice, then strain off and save the soaking water. At this point you may pasteurize this liquid portion by heating briefly to 65°C-90°C and then cooling. The choice to pasteurize or not will have a large impact on your sake making, but both options yield interesting results and are worth trying. Left unpasteurized the bacteria and wild yeast in the starter will develop unique flavors in the sake, even if sake yeast is subsequently added.

The second stage is to create the yeast starter itself. Steam the strained rice from the first step and let it cool. Add the steamed rice, soyashimizu water, koji, and yeast to a clean vessel. Allow the yeast to replicate over several days to a week, following a time/temperature/stirring routine that you are comfortable with. There are many combinations that work well, but a peak at around room temperature followed by a cooler resting phase is common. The finished starter can be added immediately to your waiting moromi, or it can be stored at fridge temperature for several weeks to condition and maintain the yeast.

Note on lactic and acetic cultures: Water kefir (25mL) is one good choice for a mixed starter culture. It contains all of the heterolactic (eg. Leuconostoc), homolactic (eg. Lactobacillus), and acetic bacteria which are key in the soyashimizu process. Kombucha, nukazuke, and many other ferments may contain similar species.

A small scale bodaimoto soyashimizu for homebrew, 2022. Photo: Mike S.

Alternative recipes: A simple one stage sake recipe has been shared by Sandor Katz via Masaru Terada of Terada Honke. Sandor’s recipe for a wild-fermented style of homebrew doburuku has single-handedly brought the obscure term ‘bodaimoto’ into the lexicon of the broader online fermentation community. See also “Sandor Katz’s Fermentation Journeys: Recipes, Techniques, and Traditions from around the World” p148-150.

How it works: There are two main pathways proposed by which starches in raw rice are broken down into the glucose and pyruvic acid needed for lactic acid fermentation. One possibility is that the required amylases and glucosidase are present in the raw rice itself.[2] Another possibility is the presence of amylolytic lactic acid bacteria (ALAB) releasing extra-cellular enzymes to convert hydrolyzed and non-hydrolyzed starches into glucose for the bacteria to carry out heterolactic fermentation.[3] Depending on the ingredients and process used, either or both of these mechanisms seem plausible.

Breweries using bodaimoto

While Bodaimoto with a capital ‘B’ has been promoted by the Nara Bodai-ken group, it does not have clear legal status tying it to one region so the term may be used by breweries elsewhere in Japan. In practice however some brands outside Nara are opting to use the term mizumoto or other identifiers. The eight breweries under the Nara Bodai-ken group display a gold label on their bottles signifying the source of their bodaimoto starter. These breweries are: Imanishi Shuzo, Yucho Shuzo, Kitaoka Honten, Yagi Shuzo, Ueda Shuzo, Katsuragi Shuzo, Kikutsukasa Jozo, and Kuramoto Shuzo.

Yucho Shuzo ‘Takacho’

Yucho Shuzo 油長酒造 is a brewery in Nara. Their current president and 13th generation owner is Yoshi ‘Chobei’ Yamamoto. A promotional video from Yucho Shuzo features bodaimoto prominently. Yucho Shuzo took part in “Taste with the Toji” #20 on 2020-10-19.

Labels - Takacho Bodaimoto Junmai - 70% milled, 17.0%, SMV: -20 to -34, Acidity: 2.9-3.5. Aged three years as nama, developing a complex and rich flavor profile. Water source hardness >250 ppm. Origin Sake provides an in depth review.

Tsuji Honten ‘Gozenshu’

Tsuji Honten 辻本店 is a brewery in Okayama. Their current toji is Maiko Tsuji.

In this article they describe their bodaimoto process in detail. Their current focus is on brewing with locally grown omachi rice and increasing the number of their product lines using bodaimoto. In the 2021 brewing year 40% of their production used bodaimoto, and in the 2022 brewing year 60% used bodaimoto and 100% of the rice used was omachi.[6]

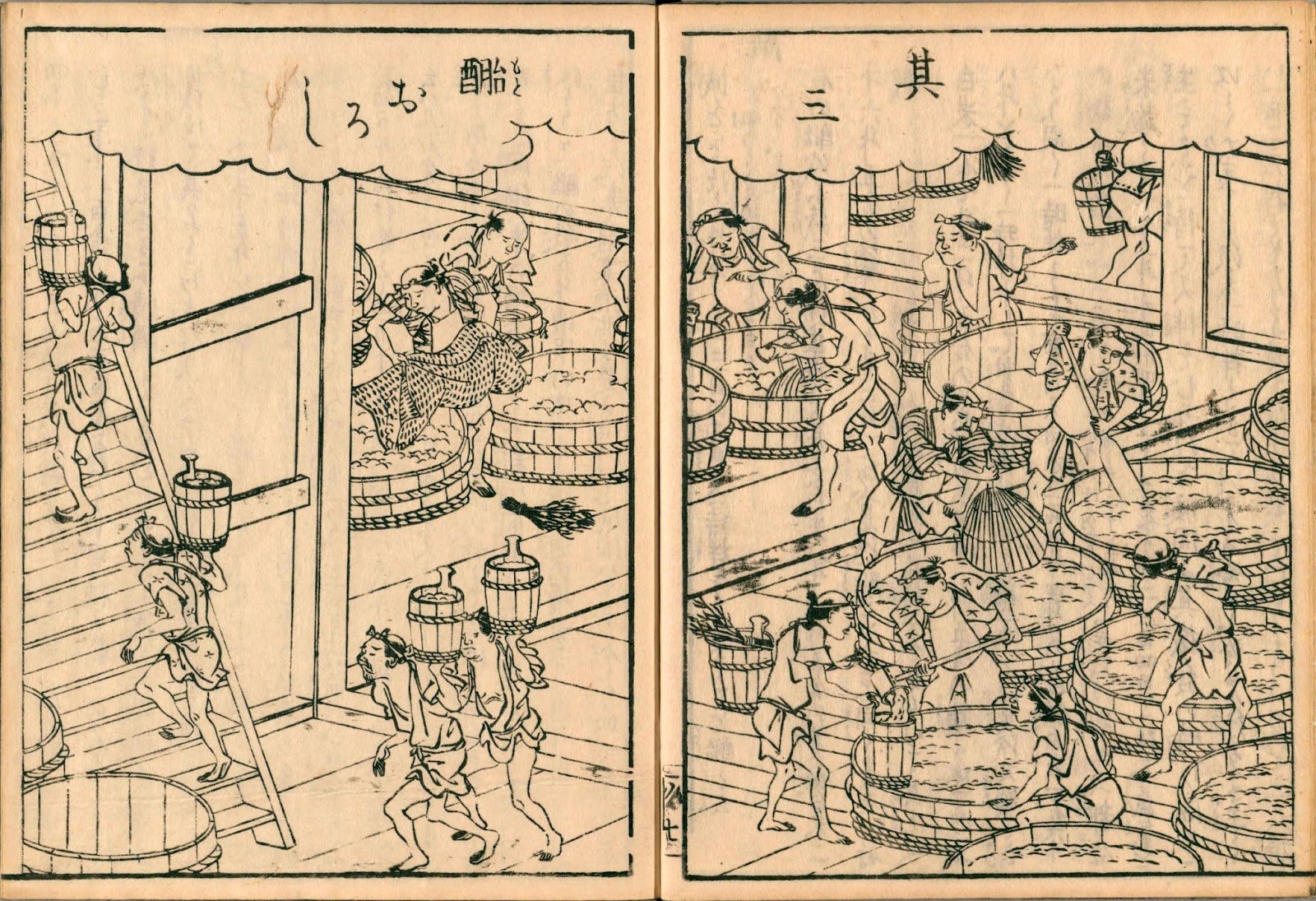

Pictured above: “Making the fermentation starter”

Tsuji Honten is credited with independently reviving the bodaimoto process from a recipe in "Nihon Sankai Meisan Zue" 日本山海名産圖會 ( 日本山海名産図会 ), written in 1799 and recovered by a relative in Britain who dealt in Japanese antiques.

Their former toji Takumi Harada began experimenting with the process in 1984, and their first bodaimoto sake was released in 1986. This article gives more background on their development process. Their early attempts to brew bodaimoto came out sour tasting and gave the impression the sake was spoiled, so changes were made to the brewing methods.[7]

Rather than adding cooked rice and raw rice to make the soyashimizu, they instead soak koji held in bags which are lightly agitated daily to release the lactic acid. They aim to reach 1.0 Sando within three days, proceeding for 10-20 days until the water reaches 5.0 Sando (minimum) up to 6.0 (total acidity). The pH can reach around 2.8, but they don’t use pH as a target itself. By running a number of experiments and comparing methods, Harada found that the use of koji sped up lactic acid production, resulting in less spoilage from unwanted microbes than when they used the traditional raw / steamed rice process. They use a ratio of only 20kg koji to 1000L water in their soyashimizu process, producing 4000L total for the year’s brewing needs in 2022. Ito explored Tsuji Honten’s process in detail in a 2014 study.[2]

The aroma of their soyashimizu starts out pungent, mellowing as it progresses. As of BY2021 they use a portion of a previously made soyashimizu to ‘seed’ subsequent batches with desirable microbes.[8] Once enough lactic acid is produced they pasteurize the soyashimizu to increase safety and lower the risk of spoilage before using it as moto brewing water.[9] They pasteurize the soyashimizu at 90°C for 3 minutes, then after cooling they introduce Kyokai #7 or #9 yeast for reliable fermentation.

Tsuji Honten took part in “Taste with the Toji” #4, #42, #100.

Labels - Complete Gozenshu bodaimoto product line

Gozenshu bodaimoto nigori nama - Omachi 65%, 17%abv, -4.0 SMV, acidity 2.1, amino acidity 1.6.

Bodaimoto x Bodaimoto kijoshu - 15%abv, -24 SMV, acidity 2.2, amino acidity 1.9.

This kijoshu uses nama brewed at the end of the prior season that has been stored cold for preservation, giving a fresher taste than a typical kijoshu.

Terada Honke

Terada Honke 寺田本家 is a brewery in Chiba established in 1673. Masaru Terada is their toji and 24th generation president. In recent times they have specialized in pre-modern brewing styles using kimoto, yamahai, and bodaimoto starters. For their bodaimoto, the soyashimizu takes about ten days to develop and appears to constitute the entire brewing water portion. Their moromi stage uses a 40% koji to rice ratio and takes two weeks to ferment, using only wild kura yeast.[10]

Labels - Daigo No Shizuku is a wild fermented doburoku using a bodaimoto method unique to Terada Honke. It is made with 90% polished koshihikari. The SMV is -15, and the acidity is a whopping 10. As with much of the sake they brew this label uses ambient yeast, ambient koji starter, and ambient lactic acid bacteria.

Their toji Masaru Terada relayed a simplified bodaimoto doburoku recipe that Sandor Katz published, encouraging many people to try making their own version.

Okura Honke ‘Kinko’

Okura Honke 大倉本家 is a brewery in Kashiba City, Nara. They make about 1800 bottles of doburoku per year using a mizumoto method that is very similar to bodaimoto. They also make yamahai under their ‘Kinko’ and ‘Okura’ labels.

Kinko traditional mizumoto doburoku (spring/summer version) - 金鼓 伝承水もと仕込み 濁酒(春・夏バージョン)

60% Kinuhikari rice from Nara, kura yeast, -25 SMV, acidity 3.5, amino acidity 3.0.Kinko traditional mizumoto doburoku (autumn/winter version) - 金鼓 伝承水もと仕込み 濁酒(秋・冬バージョン)

70% polished rice, kura yeast, -25 SMV, acidity 3.2.

Further Resources

Secrets from the Past: Talk by Prof. Eric C. Rath on Japan's oldest guide to sake brewing, Jan 2022.

Sake Deep Dive “Bodaimoto - Brewing at the Buddha's Foot”, Feb 2022.

Sake Industry News #57 - Ceremony Marks The Beginning Of Bodaimoto Season

The birthplace of sake! Sake brewing in the Muromachi period as seen at the

Bodaimoto Sake Festival at Shoryakuji Temple in Nara, Japan. Tomoyuki Amada, Sake Times, 2017.

Sake Experience Japan - Bodaimoto article and videos.

Bodaimoto entry on the Japanese-English Bilingual Corpus of Wikipedia's Kyoto Articles.

Nihonshu: Japanese Sake. Gautier Roussille, 2017, p123.

Tatsuya Kojima, Toji at Itakura Shuzo blogs here on experimenting with soyashimizu, with and without adding yeast to the moto.

References

Bodaimoto: The Renaissance of the “Enlightened” Starter. Eric C. Rath, Sake Times, Sep 2021.

Properties of microbial changes in the production of soyashimizu using rice koji. Kazunari Ito, 2014. J. Brew. Soc. Japan, Vol. 109, No. 5, p.389-396. Direct link.

Changes in compositions and microorganisms in Dakusyu-sake brewing using the Bodaimoto method. Matsuzawa, 2002. J. Brew. Soc. Japan, Vol. 97, No. 10, p.734-740. Direct link.

Sake Journal (Goshu no nikki): Japan’s Oldest Guide to Brewing. Eric C. Rath, Gastronomica (2021) 21 (4): 42–50, DOI link.

The lost 100 years of brewing aged sake Part 5, Hiroshi Yanai, Sake Times, 2018.

Taste with the Tōji #100 - Tsuji Honten session follow up, Simone Maynard, Nov 2022.

Restoration of Bodaimoto, the Origin of Modern Sake. Noriya Sumihara, 2006. Direct link.

Tsuji Honten brewery profile by Tengu Sake.

Gozenshu bodaimoto brewing process at Tsuji Honten.

Daigo No Shizuku brewing process at Terada Honke by Black Market Sake.